I wrote some months ago a post in the blog where I showed how you lose money with swings in the market of the same percentage (e.g. -10% followed by +10% or vice versa).

In another post I explained how mutual open-ended funds define and calculate their performance based on the changes in net asset value per share.

In this post I wanted to point at some fine detail: a mutual fund may have a negative performance in a period of time (e.g. a year) yet have gained positive results during the same period. How is that possible?

As I mentioned in that previous post, the net asset value per share of a mutual fund rises and decreases as the aggregate share prices of the stocks in the portfolio rise or decrease. However, each time that there is an addition of capital, it is treated as an issue of new shares at the current price. It doesn’t matter whether those shares are issued to new or old “shareholders”. Depending on whether the net asset value has increased or decreased they are acquiring the new shares at a higher or lower price than they acquired the previous ones.

If it was the case of a company, we would say that shareholders would see their share diluted. In the case of a fund, the share of the ownership is also diluted, but that doesn’t mean a reduction in the net asset value per share, since with the new investment there is an increase of the assets of the fund (and the funds will be invested). Now, let’s see it the case with one example.

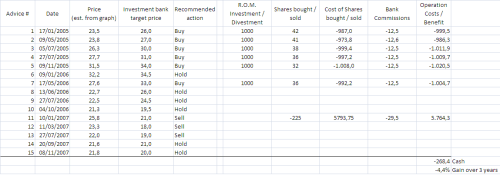

Take a fund with only one investor, A, who at the beginning of the year invested 10k€. That would be the assets of the fund at that moment. The net asset value per share could be defined as 100€, meaning that at that point there were 100 shares.

During the next months the market goes down and, along with the market, the fund’s assets. Let’s say that the reduction in value has been of 50% at half-way through the year. This means the assets of the fund would be 5,000€ (belonging to the sole investor, A). Since there were 100 shares, now the net asset value per share would be 50€.

At this low point, another investor, B, invests another 10k€ in the fund. Now, the 10,000€ would buy not 100 shares, but 200 at a price of 50€. The net asset value per share would remain unchanged at that moment, 50€. However, the assets of the fund would now be 15,000€. The total number of shares would be 300.

Imagine that during the second half of the year the performance of the fund is +50%. As I mentioned in the previous post, with consecutive market swings, -50% and then +50%, you lose. However, in this case there as been an investment in the low point and we’ll see what that means to the fund and each of the investors.

The +50% performance means to the fund an increase of its total assets up to 22,500€, or a net asset value per share of 75€ (for the same 300 shares). This is a +50% since mid-year, but a -25% from the beginning of the year. Quite a negative performance. However, the fund has received inflows of 20k€ along the year and has ended the year with +2,500€ of net gains!

For investor A: the year has meant the same -25% in both net assets and performance as he has lived through the whole period the big destruction of value in the first semester and the creation of value in the second, but, with the market swings of equal percentage value, he lost.

For investor B: the second semester has been great, as she has only lived the +50%, meaning a net gain of 5,000€.

Performance of an investment fund.

The asset manager of the fund hasn’t been in the whole a better performer allocating assets than the market, and that is what the net asset value shows. The fund has only gained in absolute terms because there was an investment at the low point.

This is nothing more than one of the points the proponents of the technique Dollar Cost Averaging defend: to invest regularly the same amounts of money to take benefit of bear markets, when the fixed amount of money may afford more shares of a given stock. In that way you don’t need to time the market to benefit of low points.

Or in another way: “Be fearful when others are greedy, be greedy when others are fearful”, Warren Buffett.