A raíz de una conversación que tuve la semana pasada recordé que tenía guardadas algunas tablas y gráficas interesantes escaneadas de la edición impresa de El País de 2010 (8 y 20 de mayo, y 17 de octubre; nunca las he encontrado en formato digital). Las comparto en el blog, porque me servirán para referirme a ellas (en conversaciones offline y online) en el futuro y seguramente escriba alguna otra entrada usando números que aparecen en ellas.

Category Archives: Economy

Brain drain or bank run?

A curiosity that comes with having a blog is that sometimes certain post starts to be read more and more and you keep wondering why. One plausible reason is clear and self-fulfilling: since the most read posts in the last few days appear at the right of the blog, readers may opt to read one of those after having read the post that brought them to the blog.

One of those post that it’s being read more and more recently is a comparison I made about income tax rates between Spain and France. I wrote it because I had some work colleagues who asked me about that, and instead of writing always the same answer I could refer them to the blog post.

See the stats below:

In this particular case, and since the post it’s written and titled in Spanish, I decided to check the stats with the dates of the announcements of the bail outs of Bankia and Spain.

Another thought I have is: since the title is relatively vague “Taxes in Spain and France” (it does not mention “income” even if it only refers to income taxes), this keeps me wondering whether people arriving at this post are tempted to emigrate from Spain or to relocate their savings… brain drain or bank run? Sigh (as in lament).

To have a better view on that, and taking into account that my blog is not a special reference nor its low readership is representative of Spain, we could simply check with Google Trends. I started to look for it, but Google’s answer was “Your terms […] do not have enough search volume to show graphs”. Sigh (as in relief).

Filed under Economy, Twitter & Media

Why do I prefer Coke

Some weeks ago I read an article about why do we prefer Coke over Pepsi by the blogger Farnamstreet (1). It mentioned a marketing initiative by Pepsi some years ago, “The Pepsi Challenge”, in which blind test were organized to see whether consumers preferred one or the other. Pepsi consistently advantaged Coke in the tests.

The article mentions other studies in which it is explained why nevertheless Coke still outsells Pepsi. In the end it seems to be due to the powerful brand Coca Cola has created along history and its association with happiness and satisfaction. This is an extreme case of what Warren Buffett describes as moat:

Definition of ‘Economic Moat’

The competitive advantage that one company has over other companies in the same industry. This term was coined by renowned investor Warren Buffett.

Investopedia explains ‘Economic Moat’

The wider the moat, the larger and more sustainable the competitive advantage. By having a well-known brand name, pricing power and a large portion of market demand, a company with a wide moat possesses characteristics that act as barriers against other companies wanting to enter into the industry.

My preference for Coke

Luca and I did this kind of blind test about 4 years ago when we lived in Madrid. We had heard of these tests and I was sure I could distinguish one from the other.

Normally, I never buy Pepsi (except when you order a “cola” at some place where there is no Coke). For the test we purchased both Pepsi and Coke, and placed them in the fridge for a while. Then I got blinded. Luca took them out of the fridge and poured each in a different glass (same kind of glass) with ice cubes. Then she offered me one glass. I tasted it.

“Ok, I don’t even need to test the other one, this is Pepsi”, I said. Then, I thought “well let’s try the other to confirm my choice”. I tasted the other glass… then I tasted again the first one. I ended up completely lost. I couldn’t tell one from the other. I finally changed my initial decision.

I was wrong in the test. Since then, I have told some friends about the experiment. Most of these friends claim they would indeed distinguish one from the other. They would probably even state that they prefer Coke due to its flavour (of course, I have no friend who prefers Pepsi! Who does?)…

After having done the test, no doubt I continue to buy Coke, but now I am aware that it is partly due to some behavioural trick being played within my mind, the kind of trick explained in the article.

—

(1) Farnam Street being the street in Omaha where Berkshire Hathaway HQ are located.

NOTE: You may want to read this case by Charlie T. Munger, Berkshire Hathaway vice chairman, about the compounding effects that led to the tremendous success of this carbonated water drink. The essay was part of a lesson he gave at USC Business School in 1994 and appears in his book “Poor Charlie’s Almanack”.

Filed under Economy, Marketing, Miscellanea

The march toward fiat money

Fiat money is “money that derives its value from government regulation or law. The term derives from the Latin fiat, meaning “let it be done” or “it shall be [money]”, as such money is established by government decree”.

The different types of money along history can be seen in this entry from the Wikipedia:

“Currently, most modern monetary systems are based on fiat money. However, for most of history, almost all money was commodity money, such as gold and silver coins. As economies developed, commodity money was eventually replaced by representative money, such as the gold standard, as traders found the physical transportation of gold and silver burdensome. Fiat currencies gradually took over in the last hundred years, especially since the breakup of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s.”

I found an interesting graphic in the book “This Time is Different” (C. Reinhart & K. Rogoff) where you can see how during several centuries governments debased or decreased the content of silver of its currency in order to get over heavy debts. The trend in the graphic seems to point at the “inevitability” of fiat money.

These debasements of course created inflation, which is nothing new, only the means have changed, as Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff say in their book:

“[…] the shift from metallic to paper currency provides an important example of the fact that technological innovation does not necessarily create entirely new kinds of financial crises but can exacerbate their effects, much as technology has constantly made warfare more deadly over the course of history.”

¿Cómo le ha ido a España en esta crisis?

Que España está inmersa una crisis seria no es noticia. Como tampoco lo es que algunas personas lo anunciaban antes de que la crisis en sí llegase.

Hace unos días terminé de leer el libro “This Time is Different”, escrito por los economistas Carmen Reinhart y Kenneth Rogoff, en el cuál leí sobre una anécdota que mencioné de la que escribí en este blog. El libro es una mirada exhaustiva a los distintos tipos de crisis financieras durante los últimos ocho siglos, cubriendo impagos de deuda pública, crisis bancarias, periodos de alta inflación, etc.

En el libro hablan dan una larga lista de indicadores que permitían ver que la última crisis en la que nos encontramos iba a suceder y citan a varios autores que así lo predijeron. Achacan por tanto la crisis a fallos en la regulación y en las políticas que se aplicaron.

Pero no es de eso de lo que quiero hablar. Sumergidos ya en la crisis, ¿cómo son las crisis?

Tras revisar multitud de casos, los autores, investigan los episodios de crisis en economías avanzadas y emergentes antes y después de la Gran Depresión y la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

La caída tras una crisis:

- La deuda crece en media un +86% (en términos absolutos) durante los 3 años siguientes a una crisis bancaria.

- Caída del precio de la vivienda en media de -35%, y un período de caída medio de 6 años.

- Bolsa: la bolsa típicamente alcanza un máximo en el año anterior de la crisis y cae durante los siguientes 2-3 años hasta un -56% en media. La recuperación es prácticamente total tres después del año de comienzo de la crisis.

- Crecimiento de la renta per cápita real: se ralentiza antes de la crisis, llegando a caer un -9% en el año de la crisis y los dos siguientes, volviendo a recuperarse en el tercer año.

- Crecimiento medio de la tasa de desempleo durante casi 5 años hasta un +7% mayor en el valle (en el caso de la Gran Depresión, ese porcentaje se elevó al 16%).

¿Y cómo le ha ido a España en esta crisis?

- La deuda había crecido un +69% desde 2007 hasta finales de 2010.

- El precio medio de la vivienda según la Sociedad de Tasación ha caído un -18% desde 2007 hasta 2011.

- El índice Ibex 35 alcanzó su máximo por encima de los 15.800 en otoño de 2007, cayendo un -56% hasta por debajo de 7.000 en marzo de 2009 (1.5 años después). Llegó a estar por encima de 12.000 en 2010, pero todavía hoy, 4 años y medio después de los máximos, no se ha recuperado (~8.600).

- La renta per cápita ha caído un -4,6% desde finales de 2008 a finales de 2010.

- La tasa de desempleo a finales de 2007 era de un 8.3%, alcanzando hoy el 22.85%, un aumento de la tasa de +14,5%.

Por desgracia, una crisis de manual, y en cuanto a las cifras de empleo especialmente drástica.

Filed under Economy

The Republic of Poyais

While I was in primary and high school, History never caught much my attention. And today is not otherwise in a broad sense, but I enjoy reading some historical notes on certain subjects.

I am reading these days the book “This Time is Different” (published in 2009), by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff (both Economics professors, the latter former economist at the IMF and member of the board of the Federal Reserve). As the description in Amazon says, the book is:

“[…] a comprehensive look at the varieties of financial crises, and guides us through eight astonishing centuries of government defaults, banking panics, and inflationary spikes–from medieval currency debasements to today’s subprime catastrophe. […]”

Being half way through it, I have had much fun with some anecdotes. I may write more about them in other posts, but in this one I want to focus in one I came across while reading the book (I have already shared it with some of you).

Let me take some excerpts from the Wikipedia:

Gregor MacGregor (24 December 1786 – 4 December 1845) was a Scottish soldier, adventurer, land speculator, and colonizer who fought in the South American struggle for independence. Upon his return to England in 1820, he claimed to be cacique of Poyais (also known as Principality of Poyais, Territory of Poyais, Republic of Poyais). Poyais was a fictional Central American country that MacGregor had invented which, with his help, drew investors and eventually colonists. […]

Gregor MacGregor went from Latin America to London, England, in 1820 and announced that he had been created cacique (highest authority or prince) of the Principality of Poyais, an independent nation on the Bay of Honduras. He claimed that native chieftan King George Frederic Augustus I of the Mosquito Shore and Nation had given him the territory of Poyais, 12,500 mile² (32,400 km²) of fertile land with untapped resources, a small number of settlers of British origin, and cooperative natives eager to please. He had created the beginnings of a country with civil service, army and democratic government. Now he needed settlers and investment and had come back to the United Kingdom to give people the opportunity.

At the time, British merchants were all too eager to enter the South American market that Spain had denied to them. The region had already become more promising in the wake of wars of South American independence, when the new governments of Colombia, Chile and Peru had issued bonds in London Royal Exchange to raise money. […]

In Edinburgh, MacGregor began to sell land rights for 3 shillings and 3 pence per acre (£0.16/acre or £40.15/km²). The average worker’s weekly wage at the time was about £1, which meant that the price was very generous. […] On 23 October 1822 MacGregor raised a loan with the total of £200,000 on behalf of the Poyais government. It was in the form of 2,000 bearer bonds worth £100 each. […]

You may read the rest of the story in the Wikipedia, but you can imagine it. Of course, Poyais defaulted on the debt issued, about 70 would-be settlers were sent to Latin America only to find that the wonderful Poyais did not exist. The group decided to come back to London. About 20 of them died in the trip and when they arrived to London about a year after departing MacGregor had already fled to France to proceed with similar schemes…

The Ponzi scheme of Madoff pales in the comparison to the one prepared by MacGregor. Beware when someone presents you with an opportunity too good to be true…

Same Old Game! (Banking)

During our last trip to London, we visited the Bank of England’s Museum (free). We enjoyed very much that visit and I may post longer about it in the future. This time I just wanted to share with you the following comic strip on display at the museum:

It was published by the weekly magazine “Punch, or the London Charivari” on the 8th November 1890 issue. In it you may see an old lady (representing the Bank of England, situated at the Threadneedle Street in London) reprimanding some young boys (commercial banks) for having played fool and got in trouble. Although the image is not very good you may read (the emphasis is mine):

Old Lady of Threadneedle Street. “You’ve got yourselves into a nice mess with your precious ‘speculation!’ Well – I’ll help you out of it, – for this once!!”

Filed under Economy, Travelling

German Debt

Yesterday, Spain issued debt at the highest yield in the last 14 years. One of the words most listened in the news lately is “spread”.

I recalled some words from my brother, months ago, pointing that absolute value of yields hadn’t changed that much as even though the spread was increasing German bonds’ yields were declining.

I wondered, how much are they declining?

Germany’s GDP is around 3,600 bn€. Its state debt is reportedly about 83.2% of its GDP, around 3,000bn€.

I checked German bond numbers in the German Finance Agency [PDF]. In the latest factsheet from end September, you may see the different auctions of different bonds and bills planned for the year and the volume of each one. You may get as well a glimpse of the debt structure. The factsheet shows how much of its 1,101bn€ in outstanding government securities are auctioned during 2011 in 1-year bills and how much in 10-year bonds (of the 1,101bn€, 275bn€ will be issued during 2011). Using that structure and the respective maturities, the composition for the whole outstanding securities can be estimated.

Note: When bonds are auctioned the coupon (interest) to be paid on them is fixed by the state, e.g., the 10-year notes have a coupon or interest paid on its face value of 2.25%. It is the yield what is variable because buyers will pay more or less for the bonds’ face value.

What are then German bond yields and latest prices paid for them? This information can be found at Bloomberg or at the Bundesbank (for a higher detail and historical yields). You may see there that 10-year bonds currently (as of yesterday) had yield of 1.78% and latest price was 104.19 euro cents, paid for a euro of face value (remember that the coupon is 2.25%, as it is stated in the German Finance Agency factsheet).

With all the previous inputs the next question is clear: How is the debt crisis affecting Germany? The fact that investors are running away from the debt of other countries (at the same time that they demand lower prices and thus increase yield of Spanish bonds) they see German bonds as a refuge: they are willing to pay more than 100 cents for a face value of one euro, making debt cheaper for Germany.

In the graphic below we can see the evolution of the 10-year bond during the last two years. It has had around 3% of average yield during that time (versus current yield of 1.78%). We can get an idea of how much Germany is saving during these troubled times.

Let’s calculate those savings. You may see in the table below, that given the estimated structure of the German debt (based on this years’ proportion of auctions by the Finance Agency), the coupons paid for each kind of bond on their face value, the prices and yields, from end June and November, Germany has achieved what would be yearly savings of about 12 bn€.

German debt: securities structure, coupons, yields, savings from end June to November (data as of Nov. 15, 2011).

These yearly 12bn€ would be saved just by the government securities (1,101bn€ outstanding), not public debt from other German institutions (~3,000bn€ in total), and only if yields continued to stay at current levels during the next issuances of debt.

As a final note: the German contribution to the European Financial Stability Facility [PDF] (EFSF) is 211bn€. Wild guess: How much of that contribution could be paid with the German debt savings if its yields stayed this low?

Filed under Economy

Impuestos en Francia vs. España

Debido a la subida de impuestos aprobada por el gobierno a finales de 2011, la tabla de este post ha quedado desactualizada. En esta otra entrada (hacer click en el enlace) se encuentra la comparación con las nuevas tablas.

***

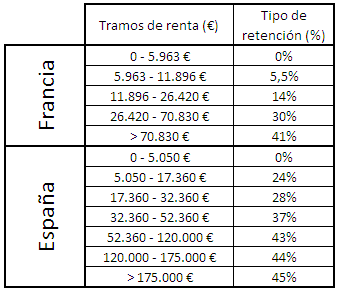

Desde que vine a Francia, varias veces me han hecho preguntas acerca de los impuestos. La última hace unos pocos días. Dado que hice la búsqueda recientemente para responder, en esta entrada simplemente voy a dejar una tabla comparativa a la que poder referirme en el futuro.

Tabla comparando tramos del impuesto sobre la renta en Francia y España (ref. 2011, ingresos de 2010)

Aclaración básica: la forma en que se interpretan los tramos es la siguiente. Por ejemplo, para un salario bruto de 35.000€, los primeros 5.983€ están exentos de retención (5.050€ en el caso de España), los siguientes 5.933€ (diferencia entre 11.896€ y 5.963€, en el caso francés) tienen una retención del 5,5%, los siguientes 14.524€ (diferencia entre 26.420€ y 11.896€, en el caso francés) tienen una retención del 14%, y así hasta llegar a los 35.000€.

En resumen, para un salario bruto de 35.000€, en Francia se pagarían 4.934€ (un 14,1%) y en España, 8.131€ (un 23,3%). En Francia se pagarían por tanto 3.198€ menos en impuestos sobre la renta.

Como veis, en Francia el impuesto sobre la renta (“IRPF”) es menor en cada tramo. La contribución que hacen los trabajadores a la Seguridad Social es sin embargo mayor (otro día pondré esa comparación), con lo que al final las cantidades son similares.

What actually happens when there is a default?

A couple of friends of mine used to point to me some months ago, jokingly or seriously, who knows, whether it was a good time to buy Greek bonds due to the hight yield they had.

My response was always the same, I prefer not to meddle with state bonds, a lesson learnt from various sources and which I wrote about some weeks ago (“Inflation and assets” and “Hyperinflation and defaults in Europe”).

I guess that with all the recent turmoil in the markets and the news, one would feel less appetite for such bonds, but I still had a question: What actually happens when there is a debt default? Is the state not giving you a monthly coupon but re-starts paying the next month? Is the payment along a year postponed and re-started the coming year? Is the principal recovered?

Last week, while flying to Amsterdam I read an insightful article from The Economist about last Argentina’s debt default. The article is an eye-opener. It gives detailed account of the different difficulties and steps that creditors are going through to recover part of their money.

But as a point of reference, take the following passage:

“Argentina’s default, after a severe economic crisis, sparked social unrest and runs on banks. It subsequently presented creditors with a take-it-or-leave-it offer of 35 cents on the dollar. They considered this derisory: previously, delinquent countries had typically paid 50-60 cents. But the government stood firm and roughly three-quarters of the bondholders took part in a debt exchange in 2005. More joined in 2010, bringing the total to 93%.”

Then, what typically happens is that monthly coupon payments are stopped and creditors are presented with a take-it-or-leave-it offer of paying them back about 50-60% of what they had invested…

The 7% who didn’t join that deal are still going through legal battles. For you and I, that most probably are not going to enter into any legal dispute with a country, we are much better off far away from state debt bonds.